Black Spots on a Chicken Comb: 10 Causes & Treatments

Chicken Fans is reader-supported. When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Learn more about our privacy policy and disclaimer.

Black spots on a chicken’s comb can look scary. There are various reasons why a chicken can carry black spots. Should you worry?

Let’s find out.

Why does a chicken have Black Spots on its comb?

The black spots on a chicken comb are usually congealed blood. The clotted blood can range from small nodules to thick, dark scabs.

A chicken’s comb is an active organ used for temperature regulation. The comb consists of multiple blood vessels and small capillaries to release body heat. That’s why Mediterranean breeds have larger combs, as they have to cope with hot weather conditions.

Since the comb is so vascular, even a minor injury can result in some bleeding. And with the comb sticking out of the body, it’s prone to damage.

This damage can come from the outside, with injuries, or from the inside, with diseases. However, most diseases won’t result in black spots but will change the color of the entire comb. Any lack of oxygen will turn the comb dark, bluish, or purple.

A well-known example is an infection with avian influenza, which causes a blue discoloration of the comb. Another example is Fowl Cholera, where chickens have a dark blue or purple coloration of the skin and comb. We will focus only on black, dark spots on a chicken comb.

Let’s see what can cause these black spots.

Peck Marks

Many times, black spots are simply peck marks on the comb. Chickens are pecking each other to establish and maintain the pecking order.

Peck marks can also result from a fight. Especially roosters tend to be involved in battles where they are pecking each other’s comb.

If the peck marks are severe wounds, you can treat them the same as fowlpox.

Sometimes, pecking can get out of hand and turn into bullying. This is often the case when putting larger birds together with smaller birds or when there is a lack of space.

When bullying is the culprit, temporarily isolating the bully or applying pinless peepers can defuse the tension. If you’re unsure how much space your flock needs, use our chicken coop size calculator.

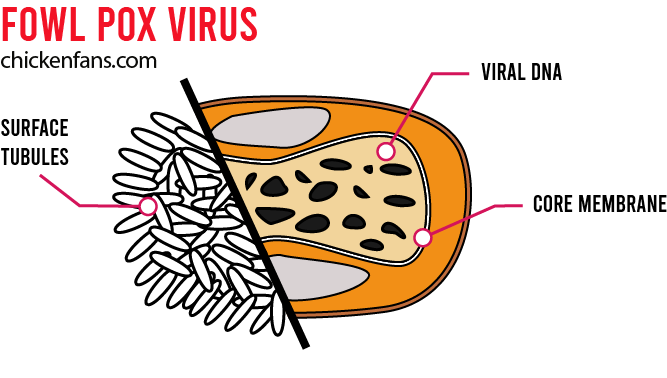

Fowlpox

Fowlpox is a disease that causes black nodules and scabs to grow on the chicken’s skin. It’s a skin infection primarily visible on the unfeathered parts of the chicken, such as the comb, eyes, wattles, and legs.

The skin disease is caused by the avian pox virus. It’s highly contagious, can be fatal for chickens, and torment a flock for many months.

The black spots differ significantly from peck marks, with the nodules and scabs evolving over time. They start as pimples, turn white or yellow, and progress into thick dark scabs. Sometimes, it grows over their eyes and blinds them. The scabs can last up to four weeks before they fall off on the ground, where they get picked up by other chickens.

Fowlpox comes in two forms: dry pox and wet pox. Only the dry form will form the typical black spots on the comb and wattles. The infection usually starts with mosquito bites. Luckily it’s not contagious to humans. Fowlpox has nothing to do with chickenpox.

Unfortunately, there is no cure yet, and vaccination is the only way to tackle it. If a chicken gets infected, you’ll have to let it run its course and soften the symptoms with supportive care.

Make sure to clean and disinfect the scabs as much as possible to prevent secondary infections. When your chickens are stressed, you can provide extra vitamin A to boost their immune response.

You can use the following products to provide supportive care for fowl pox.

- Remove dirt and loose skin but don’t force off the pox scabs. Keep black spots on the comb, wattles, and other infected areas clean and dry.

- Use MicrocynAH and antiseptic wipes to clean and disinfect the area 3-4 times daily. Remove excess feathers and clip if necessary. You can also use iodine washes such as Lugol’s as an antimicrobial treatment.

- Vitamin A supplementation can be given as adjunctive therapy to boost the immune response: 2000IU/kg or in total 10.000IU daily. Vitamin A is recommended in heat stress situations.

- Only supportive treatment is possible for dry fowl pox: you have to let it run its course. Eliminate standing water and prevent mosquitos, insect bites and fighting.

For more information on fowlpox, its symptoms, transmission, forms, treatment, and evolution, check our in-depth article on fowlpox.

Frostbite

The comb and wattles of a chicken are very sensitive to freezing temperatures. They are built to release heat, but this mechanism can turn against them in the winter. That’s why frostbite can already set in after a couple of minutes to hours of freezing temperatures, especially if it’s windy.

In temperatures below zero, the fluids inside the comb freeze and form ice crystals, resulting in blood clots. Due to lack of oxygen, the tissue in the comb starts to turn pale, then grey, and ultimately black. Sometimes the blood clots find their way to the chicken’s heart, with terrible consequences.

Chickens with large combs have less blood flowing into their combs when it’s cold, as the chicken’s body tries to keep the warmth inside. This makes them even more prone to frostbite. But even cold-hardy breeds with smaller combs can suffer from frostbite.

Usually, it’s easy to distinguish frostbite from the other causes. It’s cold outside, and frostbite starts at the endpoints of the comb.

For more severe cases of frostbite, use a healing ointment to protect and help support the comb.

Flea Infestation

Fleabites can cause tiny black spots on a chicken’s comb and wattles.

One of the most common fleas worldwide is the sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea). It’s an ectoparasite that is a pest for dogs, cats, and birds. They are about one-tenth of an inch, and the female fleas stick their head into the chicken’s skin to suck its blood.

They stay in the same position for about 19 days, and you can’t brush them off. The fleas remain attached to the chicken’s skin even when they lay eggs. The fleas drop their eggs at night in the chicken’s roosting areas. Their larvae nestle in the bedding of the chicken coop. In about two weeks, they become adult fleas, searching for a new chicken to attack.

Fleas prefer unfeathered areas, like the comb, wattles, and the area around the eyes. Their bites are painful and can lead to secondary skin infections, weight loss, anemia, and even death. Especially for young chickens, flea infestations can be fatal.

With a flea infestation, the black spots in the chicken’s comb are very tiny, and the fleas can be carefully removed using tweezers. After that, you can apply antibiotic ointment on the bite site to prevent infections.

To tackle an infestation, remove the bedding and clean the chicken coop thoroughly.

Red Mites

Like fleas, red mites are blood-sucking ectoparasites found worldwide and a plague for wild birds and chickens. They multiply at a spectacular rate and can quickly turn into an infestation.

The difference with fleas is that the mites don’t attach themselves to the skin of the chicken. During the day, they hide in the cracks and crevices of the chicken coop. They come out at night to bite and feed on the chickens for an hour. Bite marks, skin irritation, rashes, and scarring result in black spots on the chicken’s comb.

Besides the annoying bite marks, a mite pest causes stress, feather pecking, and aggressive behavior. The mites disturb the chicken’s sleep, resulting in sleep deprivation and a weaker immune system.

Treating a red mites infestation without pesticides is difficult, but you can fight the bugs with a blow torch, garlic, and disinfectant. Sealing the cracks and crevices with paraffin will also help.

- DURVET PERMETHRIN: Remove bedding, feeders, waterers and chickens from the coop. Dilute at a rate of 1 part concentrate in 19 parts water (6.4 fl. oz. per gallon) and spray on coop surface, perches, cracks and crevices,… Let dry before chickens come back to the coop.

- DIATOMACEOUS EARTH: Preventative measure against parasites in the chicken coop. Sprinkle on top of the chicken coop bedding and in nooks and crannies.

Mosquitos

Mosquito bites can also result in bite marks and, thus, black spots on a chicken comb. Apart from the bites, they can also transmit diseases like fowlpox and chicken malaria. Mosquitos thrive on pond edges with vegetation and swamps.

Although some mosquito species, like the sub-Saharan African malaria mosquito, naturally dislike a chicken’s odor, it will never prevent them from getting bitten.

It’s hard to get rid of mosquitos, but there are some measures you can take:

- avoid stagnant water like small backyard ponds

- install mosquito traps near the chicken coop

- use mosquito mesh netting

- use insecticidal spray

- plant mosquito-repelling herbs like citronella and lavender

But don’t use repellents based on chemical diffusers, as these evaporate toxic pesticides that can harm your chickens.

Next to mosquitos, stagnant water or slow-moving rivers can also cause algae poisoning in chickens. They’ll die in less than an hour if they drink contaminated water.

Other Flying Blood-sucking Parasites

There is a full spectrum of flying parasites that feed on the blood of chickens. They can all leave bite marks that turn into black spots on a chicken’s comb.

Some other examples of blood-sucking ectoparasites are:

- Biting Midge: flying parasites that feed on the blood of chickens and birds; they can transmit skin mites

- Black Fly: black flies live in tropical climates and attack your flock as a swarm. They feed on the blood of your chicken and can transmit diseases.

Favus

Favus, or avian ringworm, starts as white spots on a chicken’s comb. It’s a skin infection caused by fungi. The white spots look like powdery molds with crusts and scabs on the comb.

However, as the fungus advances and spreads to other parts of the comb, it causes a wrinkled crust. These white areas can co-exist with black spots resulting from physical damage or pecking.

Favus can be severe when it spreads to feathered areas, as feathers can start to fall out.

It’s pretty easy to rule out favus as the culprit of black spots since most of the comb will be white as if covered in flour. Also, favus is more common in chickens living in humid and damp regions.

Dirt

We’ve discussed a range of common and rare situations, from peck marks to black flies.

But the most common and apparent reason a chicken has black spots on its comb is just simple dirt. Chickens do not take water baths like humans; they bathe in dust to get clean. It’s not unusual for some dirt or mud to get stuck on the comb.

Before you start a complete diagnosis of diseases and parasites, try to see if you can get rid of the black spots by cleaning the comb. Sometimes, little sprinkles of mud can be very persistent and cling to the chicken’s comb.

Let’s wrap up and summarize everything we’ve covered.

What causes black spots on a chicken’s comb?

Black spots on a chicken’s comb are either dirt or congealed blood from injuries. Usually, they are peck marks or wounds from getting caught up in a fight. Dry scabs can be a sign of fowlpox. Tiny black spots can result from bites from parasites like fleas, red mites, and mosquitos. In freezing temperatures, black spots can be frostbite.

When the spots look like dry scabs that start with a lighter white or yellowish color, it’s probably the dry form of fowlpox, a contagious disease. Fowlpox has no cure, so you have to let it run its course.

Black spots are a symptom and can result from many injuries, including flea manifestations or mosquito bites.

However, dirt or peck marks are the most common reason to see black spots on your chicken’s comb.

If you want to read more about chicken health problems, symptoms, and diseases, check out our ‘Health Page‘. You’ll find a ‘Symptom Checker‘, a complete list of ‘Chicken Behavior‘, and an overlook of the most common ‘Chicken Diseases‘. Or go to ‘The Classroom‘ and find a comprehensive list of all Chicken Fans articles.

Dr. I. Crnec is a licensed veterinarian with several years of experience. She has published work on the effect of vitamin supplementation, egg-laying performances of chickens under heat-stress conditions and the effects of calcium supplementation on eggshell strength.