Linebreeding, Inbreeding & Outcrossing

As a breeder, you have a couple of possible ways to set up for selective breeding. They all come with their own advantages and trade-offs. How are the genes passed? What are the pitfalls? What’s the best way of mating birds?

Let’s discuss.

- Breeding and the Gene Pool

- Chicken Genetics

- Breeding Strategies

- Outcrossing

- Linebreeding

- Mating Strategies

- Relatedness and Blood Percentage

- Summary

Breeding and the Gene Pool

All plants and animals contain unique genetic codes that define their characteristics. Although members of the same species share a lot of their DNA, a significant portion is still variable. This genetic diversity is considered advantageous for the survival of the species. It decreases the sensitivity to environmental change, and diversity allows for multiple improved varieties.

That said, many chicken breeds we know today have been created by tailoring the genetic makeup to produce a single variety with specific desired characteristics. The traditional method of gene manipulation is selective breeding and has been around for thousands of years.

Genetic diversity in chickens

The total gene pool and genetic diversity of chickens, in general, is enormous. There are many different breeds with all other characteristics. These breeds have been bred to the exact genetic elements that define the breed’s perfection. Nobody wants genes for long legs in a Rosecomb, nor do we want genes for short legs in Game Fowl. And we certainly don’t want any genetic diseases in our breeds.

In recent years, many biotechnological advancements allowed for new types of genetic manipulation. Genetic engineering techniques like molecular cloning or gene editing with CRISPR are shaping our future. However, all successful breeders in the past have been using the systems of linebreeding and inbreeding. And these methods will still exist for a long time. Breeders continue to carry out serious linebreeding programs to keep desired qualities and characteristics and eliminate undesirable traits in a breed.

Chicken Genetics

Before diving into the nitty gritty details of inbreeding, let’s have a quick glance and recap at chicken genetics.

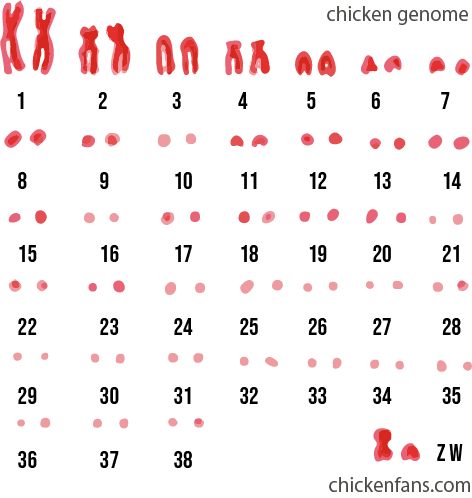

The DNA of chickens, with their genetic code, is stored on chromosomes. Chickens have 39 chromosome pairs. Thirty-eight pairs are homologous chromosomes, and one pair are sex chromosomes (Z/W).

These chromosomes contain the genes that define the characteristics of a chicken. Because the chromosomes come in pairs, every chicken has its features defined twice. The expression of a gene on a chromosome is called an allele.

When a chicken has two identical alleles of a particular gene, it’s called homozygotes. For example, when a blue-legged bird carries twice the genes for only blue legs.

On the contrary, when a chicken has different alleles corresponding to chromosomal loci, it’s called heterozygous. For example, when a blue-legged chicken has genes for blue legs as well as green legs.

A strain of chickens is a specific variety of a chicken breed obtained after successful inbreedings.

Breeding Strategies

With selective breeding, chicken breeders have a couple of possible breeding strategies:

- Outcrossing – breeding chickens that are unrelated to each other. Outcrossing or outbreeding is the mating of animals that are members of the same breed or variety but don’t have any family bond. Mating chickens of different breeds is also referred to as outcrossing or crossbreeding, but we won’t dive into that. Sometimes, crossing a chicken in a distant part of the family line is also called outcrossing. It’s a safe way to add new blood with the least amount of retrogression compared to linebreeding.

- Linebreeding – breeding with closely related chickens to create a single exceptional animal. This breeding method keeps the offspring closely related to some highly admired ancestor that started the breeding iterations. Linebreeding involves inbreeding and can mate sire to daughter, son to mother, brother to sister, etc. Multiple pens are continuously re-used, and there is usually a lot of culling going on. Linebreeding is technically the strategical application of inbreeding.

- Inbreeding or Close Breeding – refers to breeding chickens that are more closely related than the average chickens of a specific breed. Inbreeding includes mating sire to daughter, son to mother, and full brother to full sister. The terminology becomes a bit fuzzy when crossing half-brother, half-sister or cousins, aunts, uncles and grandparents. Some will call it inbreeding and some would say it’s linebreeding. There is not a single perfect definition, and it’s instead a continuum in degrees of family relationships of the same chicken breed.

Not-so-close inbreeding would be anything like grandfather to granddaughter, grandson to grandmother, uncle to niece, aunt to nephew, cousin to cousin, half-brother to half-sister. That’s opposed to very close inbreeding, which includes breeding daughters back to their fathers for successive generations, sons to their mothers, or brothers to sisters.

Outcrossing

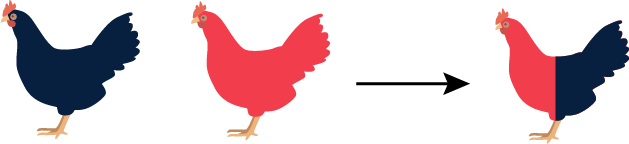

Outcrossing is breeding chickens that are unrelated, which minimizes the chances of undesirable traits that can occur with inbreeding. Unfortunately, the heterozygous nature also reduces the chances for any desirable trait. Unrelated chickens have a higher chance of being heterozygous with unmatching gene pairs (e.g., green and blue legs). Outcrossing creates gene diversity, and while an outcrossed bird may be an outstanding performer, it is less interesting for breeding stocks. The best outcrosses start with a pure strain chicken that is strongly linebred.

Sometimes outcrossing can produce an excellent bird with desired characteristics, almost by accident. However, due to their heterozygous nature, it’s unlikely that they will breed true.

Timing of an outcross

After many generations of inbreeding, it can be time to outcross in order to get fewer blood-related connections. There is no real rule on when exactly it’s time to start an outcross. But the longer any linebreeding is going on, the higher the chances for defects.

Every outcross represents a danger, especially if the outcross is made with an entirely unrelated strain. After every outcross, the birds should be bred right back into the original strain.

A successful outcross can and should only be made when:

- there are several iterations passed of inbreeding

- the ancestors and genetic composition of the external bird are known

- the external bird and ancestors have desirable traits to introduce into the mix

- the external bird is a superior animal to work with

- the breeding got stuck, and the resulting chickens are not what was hoped for

An inexperienced breeder might throw away all of the initial inbreeding efforts when mismanaging the outcrossing.

Outcrossing is commonly believed to improve vigor. However, linebreeding can improve vigor too, as it’s one of the desirable qualities that’s been selected for. Close inbreeding is full of dangers, but it can also bring great rewards.

Linebreeding

The main linebreeding principle is: “breed like to like to get like”. Working with the same set of birds for multiple iterations allows breeders to create a chicken type in the shortest time possible.

However, there is a danger with going all-in on linebreeding.

Let’s say you want to create the best egg layers in town. By continuously selecting the best egg layers of the flock, you will get more and more eggs over generations. At the same time, if these chickens are consistently bad-tempered, breeding like-to-like results in an intensified line of poor-dispositioned chickens.

Inbreeding

Inbreeding is breeding chickens that are closely related to each other, like brother and sister or father and daughter.

The advantages of inbreeding are:

- it’s the quickest method of fixing desirable characteristics

- it tends to generate strains that are uniform in type

- it generates birds that are closely related to the original ancestor

- it’s easier to predict the results of breeding with careful genetic knowledge

The disadvantages of inbreeding are:

- higher chances of genetic abnormalities

- a high number of undesirable breeding stock and thus a lot of culling

- it requires a lot of skill and genetic knowledge from the breeder

Linebreeding is, in essence, the application of multiple iterations of inbreeding. It’s a quick way to create superior chickens, especially if the birds are not susceptible to diseases. Linebreeding with inbreeding is the only way to produce homogeneous offspring and consolidate the best traits.

Inbreeding pitfalls

One of the pitfalls of linebreeding is to hyper-focus on the characteristics but neglect any physical, functional, or behavioral aspects of the birds. Many beginning breeders only have an eye for the winning combinations in terms of how the birds look. Close inbreeding should also focus on the faults. Serious breeders study all the good and the bad properties the pedigrees represent. Next to looks, vital health and desirable temperament is equally important.

Other common mistakes include:

- starting with the wrong stock

- not knowing the genetics of the birds they start with

- not knowing how to assess whether a bird is a good individual

Mating Strategies

When mating chickens, any breeder has a couple of options. It’s up to the breeder to choose the correct mating tactics for the desired outcome.

- Assortative Mating – mating like to like based on similarities, not necessarily looking at the family line. The goal is to create a bird that resembles its parents.

- Negative Assortative Mating – mating chickens of different phenotypes with different characteristics. The goal is to breed offspring that is not as extreme as either parent

Relatedness and Blood Percentage

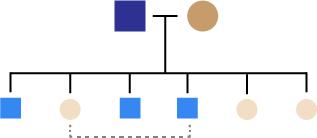

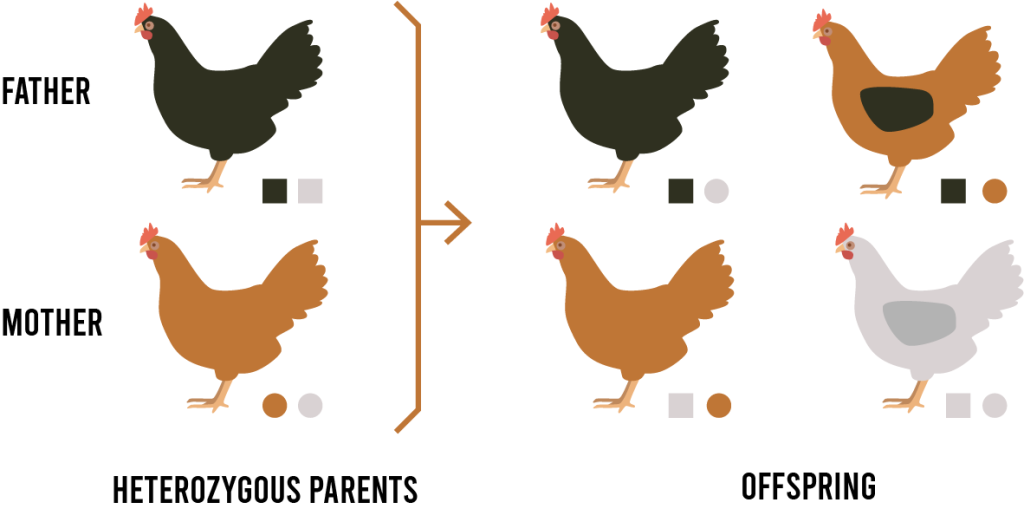

Any chick will get half of its genes from its mother hen and half of its genes from the father. That’s why offspring always resemble the parents. The relatedness or inbreeding coefficient is 50% from the parents to their chicks.

Full siblings generally share half of their genes, but that doesn’t have to be the case. The offspring can have four possible gene outcomes when the parent is heterozygous for different alleles. Either the siblings have no genes in common, either they have all in common, or they have 50% of genes in common. It’s impossible to predict the number of genes the siblings will have in common.

When you extrapolate this to more distant family members, half-siblings on average share 25% of their genes and first cousins about 12.5%. Every generation, the relatedness halves.

The further you get, the smaller the chance that specific genes are passed on. However, if the same chicken is used multiple times with inbreeding, the chances are much higher of passing specific genes.

Inbreeding Comparison Examples

So far, it has all been pretty theoretical. To get a better understanding of inbreeding dangers, let’s have a look at an example.

The first situation is a mating example that starts with a completely unrelated hen and rooster. Every time they get a daughter, the pullet is bred back to the original father for every successive generation.

This results in the following inbreeding coefficients that gradually increase to 50%:

| Generation | Inbreeding Coefficient |

|---|---|

| 1st daughter | 0% |

| 2nd daughter | 25% |

| 3rd daughter | 37,5% |

| 4th daughter | 43.7% |

| 5th daughter | 46.9% |

| 6th daughter | 48.4% |

| 7th daughter | 49.2% |

| 8th daughter | 49,6% |

A second situation starts with an unrelated pair of chickens. Then every generation after it, the brothers and sisters are mated. This gives the following inbreeding coefficients already reaching 50% in the 4th generation.

| Generation | Inbreeding Coefficient |

|---|---|

| 1st generation | 0% |

| 2nd generation | 25% |

| 3rd generation | 37.5% |

| 4th generation | 50.0% |

| 5th generation | 59.4% |

| 6th generation | 67.2% |

| 7th generation | 73.4% |

| 8th generation | 78.5% |

So the first few iterations are generally safe, and there is not much difference between parent-offspring matings and brother and sister mating. But after a couple of iterations, the mating of brothers and sisters escalates quickly. That’s why breeding parents to offspring is generally better than breeding siblings.

Summary

The genetic diversity of chickens is enormous, and there are a lot of different breeds and varieties around. To create a bird with specific qualities, breeders have a couple of options.

Linebreeding is standard practice and uses closely related chickens to create a single exceptional animal. Linebreeding uses inbreeding as a tool for meticulous selection and to produce a homogeneous offspring that can breed true. After a couple of iterations, breeders use outcrossing to lower their chances of genetic abnormalities.

When done correctly, linebreeding is not as bad as many make it out to be. It’s perfectly possible to select for vigor by choosing the absolute healthiest and most vigorous stock year after year. Even as low as 1/8 different blood can be enough to ensure diversity. Whether you use linebreeding or outcrossing, it’s always important to keep an eye on the good and bad characteristics of the flock.

We also discussed mating strategies for close inbreeding. It’s a safer choice to breed parents to offspring rather than use close inbreeding solely with siblings.