Egg Color Genetics

Chickens can lay eggs in all colors, including white, brown, blue, green, and even pink. But how do the eggs get this color? And how much is genetically defined?

Scientific research added a lot of insights in the last decade.

Let’s have a look at egg color and explore chicken genetics.

- How does an egg get its color?

- Chicken egg genetics

- White eggs

- Brown eggs

- Blue eggs

- Olive eggs

- Pink eggs

- External factors

- Summary

How does an egg get its color?

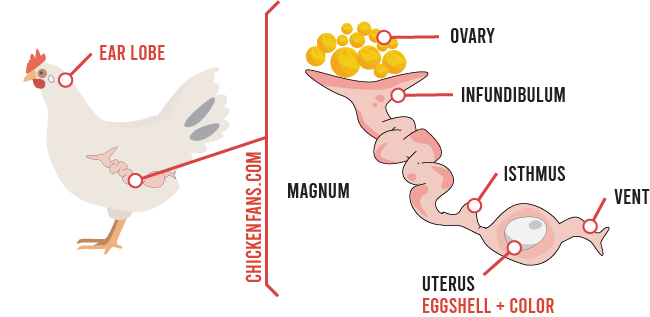

The pigments of an egg reside primarily in the shell, membrane, and the protective bloom that covers the egg. It takes about 24 hours to form a whole egg from a yolk. Twenty of those hours are reserved for the eggshell to develop in a chicken’s uterus or shell gland. But it’s only in the last few hours the shell is colored.

The eggshell gets its color from two pigments:

- Brown pigment, protoporphyrin, which is derived from hemoglobin in the blood

- Blue-green pigment, biliverdin, which is derived from bile

The genes of the chicken define the mixture of these pigments in the shell. All colors combine those pigments, sometimes with the influence of other reddish tints in the egg membrane (all protoporphyrin based).

The earlobe’s color often reveals the color of the eggs, but not always. For example, most chickens with white earlobes will be white egg layers. However, this doesn’t always hold. Lamona chickens have red ear lobes and lay white eggs. Penedesencas lay very dark brown eggs but have white ear lobes.

Chicken Egg Genetics

The color of the egg is mainly defined by genetics, although some external factors may also influence the egg color.

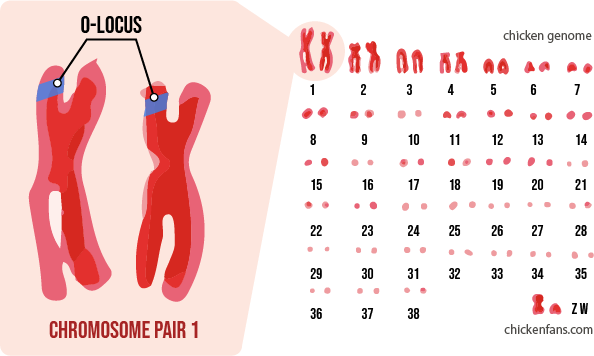

Chickens have 39 chromosome pairs in their DNA that contain genetic information. These genes define the characteristics of the chicken, and a couple of them affect the egg color.

On chromosome 1, there is a specific spot with a gene that regulates blue eggs. It’s called the O-locus, and the scientific name is SLCO1B3.

This spot can have two values, O and o:

- Dominant Blue (O): chickens with O will have blue pigment in their eggs

- Wild Type (o+): the default value of the gene inherited from junglefowl does not generate blue eggs

O is dominant, so if one of the chromosomes in the pair has O, there is already some blue pigment in the eggs. A hen that carries two O-genes has a lot of blue in her eggs.

The brown egg pigments are a little bit more complex. There are at least 13 genes that code for brown eggs, spread over several chromosomes.

White Eggs

White eggs are eggs that lack any pigmentation on the shell. The white color comes from the calcium carbonate in the eggshell. About 95% of the eggshell is calcium. The rest of the shell is made of minerals and proteins. That’s why laying hens need extra calcium supplementation.

White egg layers have a gene on the blue pigment O-locus, but it’s the wild-type gene. The Red Jungle Fowl (Gallus gallus), considered the ancestor of chickens, also lays white eggs. So this wild-type gene is the non-mutated, standard version that has existed in nature for ages.

White eggs also lack protoporphyrin, the brown egg coloration pigment. This pigment is derived from heme in chickens. Heme is a chemical compound used by the body to create hemoglobin, the protein that transfers oxygen in the blood. In chickens, heme is made in soft bone tissue in the spongy regions of the bones and in the liver.

The brown protoporphyrinogen pigments and heme have their own transporter protein in the body: histidine-rich glycoprotein. This protein is linked to a specific gene on chromosome 9, the heme-responsive gene-1 (HRG1). In 2014, researchers discovered that high-level expressions of HRG1 are associated with white eggshells.

Brown Eggs

Brown eggs come in several variations, from slightly tinted to dark brown. The brown protoporphyrin pigments are added to the eggshell in the shell gland. This only happens in the last stages of eggshell formation. The result is a thin brown layer covering the egg like paint.

The inner shell is still white, and you can easily scratch the brown color with a fingernail. When the egg is fresh in the nesting box, the brown surface layer can be scratched by bedding material like pine shavings.

The brown color is associated with multiple genes, both coloring, and suppressing. These genes control the processing of heme to brown protoporphyrinogen pigments:

- Transporters for both protoporphyrinogen and heme: Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) which refers to ABCG2, feline leukemia virus receptor (FLVCR), and heme-responsive gene-1 (HRG1)

- Rate-limiting enzymes for the heme-biosynthetic pathways: Coproporphyrinogen III oxidase (CPOX) and ferrochelatase (FECH)

- Organic anion transporting polypeptides: SLCO1C1, SLCO1A2, SLCO1B3 and LOC418189

High-level expression of BCRP is associated with brown egg colors.

Although there are many scientific advances in the field, the synthesis and deposition of brown pigments in the eggshell is still unclear. Since protoporphyrin is closely related to heme, scientists used to believe that the pigment was released by red blood cells when they died. Current research indicates that shell pigments are created in a chicken’s shell gland.

Blue Eggs

Why bother with brown eggs if you can have blue eggs. Genetics become really interesting when we look at blue eggs.

Chickens that lay blue eggs have Dominant O in their genes on chromosome 1. This factor is called Oocyan, that’s why it’s written with the letter O. There is also a gene called Bl, for Blue, but this controls plumage color and has nothing to do with the eggshells.

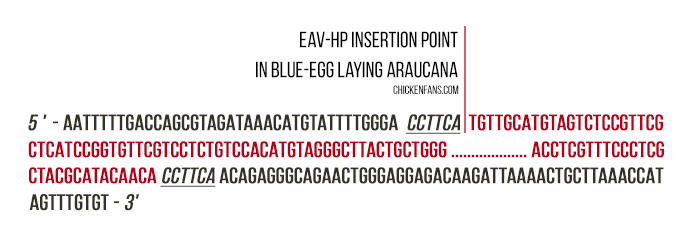

The blue pigment gene sits on chromosome 1, and the scientific name for the region is SLCO1B3. In 2013, researchers discovered the DNA pattern linked to the blue egg pigmentation in this region. It turns out that this part of the DNA is an ancient chicken virus called EAV-HP.

This little part of viral EAV-HP DNA creates proteins that transport greenish-yellow bile salt containing biliverdin pigments. The transporter proteins deposit the biliverdin into the cells when the eggshell develops in the uterus, which ultimately results in blue eggs.

EAV-HP Virus

The EAV-HP is an ancient retrovirus that affected the Gallus-ancestors of chickens. There is an active spread of the viral DNA, but the virus itself is inactive. None of the proviruses has been observed to produce infectious virions. However, under the influence of a helper virus, it is believed to have led to the emergence of the avian leukosis virus. It’s a virus that can lead to cancer, and it causes significant economic losses in the poultry industry.

As if carrying viral DNA is not strange enough, this mutation even happened twice in the history of chicken breeds. It turns out that South American/European chickens evolved separately from Asian chickens. Both contain the viral EAV-HP in their DNA in the exact same location, but the Asian breeds have the gene inserted in the opposite orientation on the complementary DNA strand of the double helix.

Both mutations started laying blue eggs and have probably been part of selective breeding programs. This makes blue eggs in chickens a perfect example of convergent evolution in chicken breeds.

Pea Comb & Blue Eggs

The gene for pea combs (P) also sits on chromosome 1, very close to the O-gene location. You can see this if you inspect the areas on the chromosome linkage map.

Pea combs and blue eggs usually come together because:

- they are both dominant characteristics

- they are located closely together on chromosome 1, and there is a small chance for cross-over events

Cross-overs are genetic recombinations that happen during cell division in sexually reproducing organisms. Since the genes are so close together, they usually stick together.

That said, the pea comb gene and the blue eggs are two different genes, so they don’t always have to come together. However, because both the pea comb genes and blue egg genes are dominant, it takes a while to get white eggs, or single comb crosses when you start mating with pure breeds.

Olive Eggs

Some chickens are olive eggers and lay greenish eggs. These eggs are blue eggs with a coating of dark brown pigment. The blue color is found all through the shell, which is evident if you look at the inside of the eggs. The combination of the blue shell and brown coating turns the outside of the egg green.

To breed an olive egger, you need the genes of a brown layer and a blue layer. A typical way to produce olive eggers is to crossbreed Araucanas or Ameraucanas with Marans. The offspring is usually not immediately laying dark green eggs. That’s why the pullets are often bred back to their Marans fathers to produce beautiful green eggs.

Pink Eggs

Some breeds, like the Croad Langshans, are known for their plum-colored and purple eggs. Sometimes you can also see the purple shine on the eggs of olive eggers.

The pink color comes from the bloom that covers the eggs. The bloom, or cuticle, is a protective cover that lays on the surface of the egg to protect it. It’s the egg’s last coating when the eggshell is completed in the shell gland. It prevents bacteria from entering the egg, which is the primary reason you should not wash your eggs.

When a thick layer of bloom covers a white eggshell, the egg gets its pink color. If the eggshell contains any protoporphyrin, the result is rather purple. The pastel coating only shows when the bloom dries. When the bloom is still wet, it’s transparent, and you see the standard shell color.

Genetics of the Pink and Plum-colors

The pink color in the cuticle result from the pigmentation of brown to greenish colors combined with fluorescences of red to pink. The strengths of this fluorescence vary and depend on the breed. The same porphyrin pigments that color the egg also play a role in the color of the bloom.

The exact genetic coding of the pink color in the bloom is yet to be unrevealed. In 2018, researchers found that the color and quality of the bloom are related to the pigments and quality of the eggshell. The correlation is strong enough to use the bloom quality as a way to measure the egg quality.

An eggshell is made of calcium carbonate crystals and has thousands of tiny pores. While the bloom protects the egg from bacteria, the bloom itself can also be soaked into the pores of the egg. The pink pigments of the bloom may permeate the eggshell through these pores and mix with the actual shell color.

External Factors that influence egg color

While the egg color is defined in the genes of a chicken, the actual color of the egg can be influenced by a couple of external factors:

- Medical conditions: several diseases can influence the shell formation process, either direct or indirect. A defective shell gland or an oviduct inflammation (salpingitis) will directly impact the eggshell. Medical conditions such as Egg Drop Syndrom, Infectious Bronchitis, Ochratoxicosis, and Osteoporosis disrupt eggshell mineralization and colorization. Most diseases will also result in thin-shelled eggs or soft shell eggs.

- Food and medication: food intake has more of an influence on the egg yolk color. Some deficiencies, like vitamin D3 and Manganese deficiencies, can influence the eggshell formation process, resulting in lower quality, thin-shelled eggs. Medication like Nicarbazin can also affect the pigmentation of the eggshell and bloom. Nicarbazin is a broad-spectrum antiprotozoal agent used against coccidiosis. It causes a mottling of the egg yolks, and a 5mg dose can already cause pale eggshells within a day.

- Age: when chickens grow up and age, the egg size follows. Less pigment for bigger eggs will result in lighter eggs. When they approach the end of their laying, the egg-laying machinery slowly deactivates, influencing the egg color.

- Light: sunlight provides chickens with vitamin D3. It’s synthesized from ultraviolet light and is vital for eggshell formation. Eggshell quality tends to be optimal when laying hens receive 14 to 18 hours of natural daylight. The light regulates important hormones that orchestrate eggshell formation. When days are prolonged with artificial light, the eggs tend to be lighter colored. The same holds for free-ranging chickens that receive plenty of sunlight.

- Stress is one of the most common factors that disturb the egg-laying process. It can cause delayed egg laying and eggshell abnormalities. Stress can also cause early egg laying, not giving the uterus enough time to form a thick pigmented shell.

Due to selective breeding, many birds are now high-performing egg-laying machines. The eggs of these birds can have shorter production times and spend less time in the shell gland, leaving it with less pigment.

Summary

Chicken eggs get their color from two pigments, a brown pigment, protoporphyrin, and a blue pigment, biliverdin.

The brown color covers the surface of the shell like paint. It’s deposited in the last hours of eggshell formation in the shell gland. Several genes code for brown, giving us a wide variety of brown egg shades. Most of the egg pigmentation process is not yet scientifically understood.

The blue egg color is coded by parts of the ancient EAV-HP retrovirus sitting in the chicken’s DNA. The virus is inactive, but breeds carrying the mutated gene have their blue pigments unlocked and produce blue eggs. The blue egg gene resides at the o-locus on chromosome 1, and chickens having two copies on each chromosome lay the most profound blue eggs. Whereas the brown pigment sits on the surface, the blue color is found throughout the shell.

When blue eggs get a brown cover, the resulting eggs look olive. Therefore, breeds with both blue and brown genes will lay green eggs. Olive eggers are popular in breeding programs, where dark egg layers like Marans are crossed with blue eggers like Araucanas.

As if that’s not enough, there is also a colored bloom covering the egg to protect it from the infiltration of bacteria. This bloom, or cuticle, contains fluorescent pigments that can give the eggs a pink or plum-colored look when it dries.

The intensity of the egg color can vary under the influence of external factors such as sunlight exposure, food intake, medication, or stress.

If you want to learn more about chicken breeds that lay colored eggs, check out our article ‘10 Popular Chickens With Colored Eggs‘.

Further Reading

If you liked this article, these might be an interesting read as well:

- 12 Reasons Chickens lay Soft Shell Eggs: a deep dive into the eggshell formation process and why you might encounter thin-shelled or soft shell eggs.

- How To Wash Fresh Eggs: why you should probably not wash fresh eggs and how to store them

- Chicken Breeding and Genetics: beginner’s guide into the wonderful world of chicken genetics and breeding