Chicken Digestive System

The chicken’s digestive system consists of several organs working together to break down food. A basic understanding helps to recognize everyday situations, like a bulging crop or brown cecal droppings. It also helps to identify unusual conditions and to understand how several diseases affect the health of your chickens.

We cover everything there is to know about the chicken’s digestive system.

- Overview of the Chicken Digestive System

- Organs in the Chicken’s Digestive System

- Chicken’s Digestive System vs. Human Digestive System

- Growth of the Digestive System in a Chicken Embryo

- Appetite Regulation in Chickens

- Control of the Chicken’s Digestive System

- Summary

Overview of the Chicken Digestive System

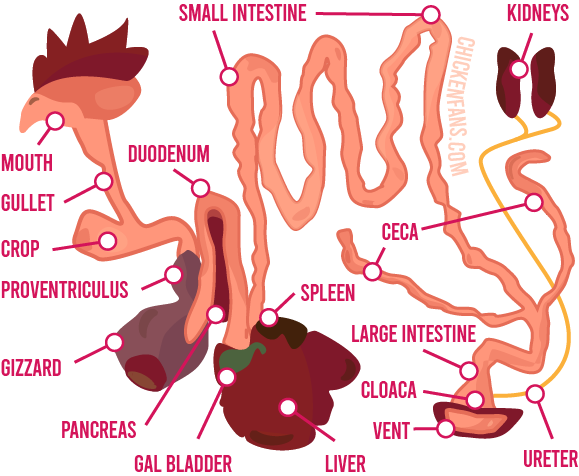

The goal of the digestive system is to mechanically and chemically break down food into nutrients for the body. The food enters via the mouth and travels through a long, tube-like alimentary tract until it reaches the chicken’s vent.

A chicken’s digestive system is similar to ours but not entirely the same either:

- chickens don’t have teeth and can’t chew

- they carry particular organs like a crop, two ceca, and a gizzard

- they don’t urinate and have two different kinds of poop

- their eggs and droppings pass through the same opening.

Chickens always seem to be hungry and eat all day long. Their appetite is regulated in the brain, and several hormones regulate digestion and satiety.

Organs in the Chicken’s Digestive System

The digestive system is a complex interplay of many organs. For the discussion, we’ll travel along with the food, starting with the beak and mouth.

Beak

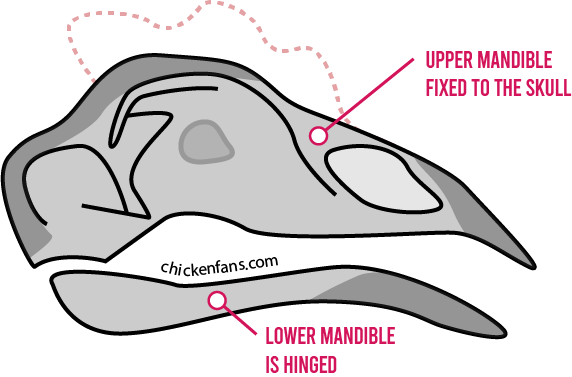

Chickens don’t have any teeth or cheeks. Instead, they have a beak consisting of a keratin layer on top of the underlying bone. They can pick up food but can’t chew on it to break it into pieces.

The upper mandible is fixed to the skull, while the lower beak can be moved to grab food. Sometimes chickens shake their head to rip their food into pieces.

Mouth

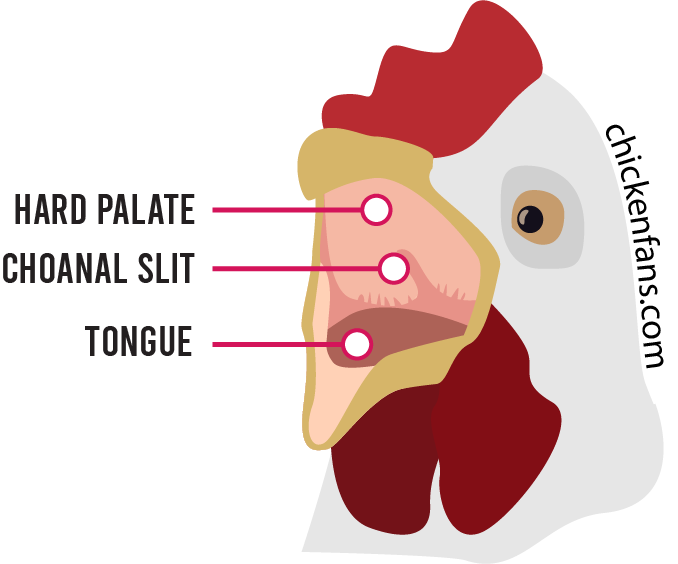

On the inside of the beak, they have a hard palate with a choanal slit that connects the mouth to the nasal cavities.

They don’t have a soft palate covering the slit and can’t vacuum their mouths to swallow water like us. Instead, they elevate their head and let the water run down their gullet. Some diseases like canker can cause sores in the mouth to grow through the slit, sinuses, and skull base.

Chickens have a tongue with a couple of tastebuds, so they can taste their food, although it’s not as well-developed as our taste.

They also have a lot of saliva glands in several places in their mouth. The saliva starts the chemical breakdown of carbohydrates in the feed. It also moistens the food, so it’s easier to swallow.

Gullet and Crop

The gullet, or esophagus, is a flexible pathway lubricated with mucus for the food to slide through.

When chickens swallow, their food doesn’t go straight through their throat to the stomach. Halfway the food passes the crop, a balloon-like space where chickens buffer their food. The crop allows them to eat whatever they can while the digestion progresses at a steady pace.

After a full day of eating, you can feel the crop as a big lump on the breast bone. The crop can swell to the size of a tennis ball, which can feel strange for people that are unaware chickens have a crop.

Food can stay up to 12 hours in the chicken’s crop. When they roost at night, their digestion keeps running, and the crop should be empty in the morning.

An impacted crop is a condition where food gets stuck in the crop, and the passage is blocked. Sour crop, or candidiasis, is a yeast infection of the chicken’s crop. A pendulous crop is a condition where the muscles of the crop are overstretched, and the crop gets too large.

Stomach, Proventriculus, Gizzard

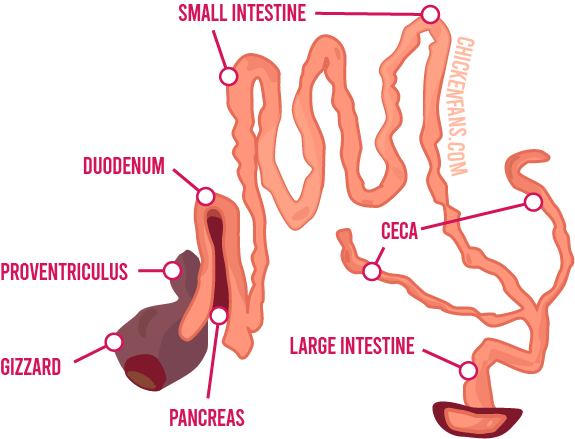

When food leaves the crop, it enters the proventriculus. This long-shaped organ is the first part of the chicken’s stomach.

The chemical digestion of proteins starts in the proventriculus. It produces hydrochloric acid and pepsins, which break down proteins and other structures of amino acids. The proventriculus has a thick wall to cope with the acids.

The second part of the stomach is the muscular gizzard. It contains grit and small stones that aid in breaking up the food. The inner surface of the gizzard is made of keratin-enforced solid skin that can cope with the food’s destructive grinding.

Liver

The liver is a large organ in chickens and lies next to the gall bladder and spleen. It serves multiple purposes and is involved in critical biochemical processes for digestion and metabolism. The condition of the liver is crucial for the health of our birds.

The functions of the chicken liver include:

- Synthesis of fat and proteins to be used anywhere in a chicken’s body.

- Creation of bile, stored in the gall bladder, for fat processing.

- Conversion of sugars into fats, lipogenesis. Poultry feed is usually low in fat.

- Maintain blood sugar levels and convert glucose to glycogen when blood sugar becomes too high. Chickens have high blood sugar levels because they are active all day.

- Storage and production of vitamins. Vitamin K is utilized in the liver for blood clotting. Vitamin B is produced in the liver.

- Some production of red blood cells, but most are created in bone marrow

- Getting rid of toxic substances in the food such as pesticides, drugs, antibiotics, and heavy metals

Chickens have a complex bile secretion system which allows them to digest food continuously. Dogs and cats, for example, don’t need continuous bile secretion to the intestines as they only eat once or twice a day.

Small Intestine

The small intestine starts from the gizzard and is about 55 inches long.

The large size creates the necessary space for :

- enzymes to further digest the food

- absorption of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats through the inner surface of the intestines

The first part of the small intestine is the duodenum. It’s about 8 inches long (~20cm) and makes a duodenal loop. In the middle of the loop lies the pancreas, which secretes digestive enzymes that work in the small intestine. These enzymes break down proteins, fats, cholesterol, starch, and sucrose.

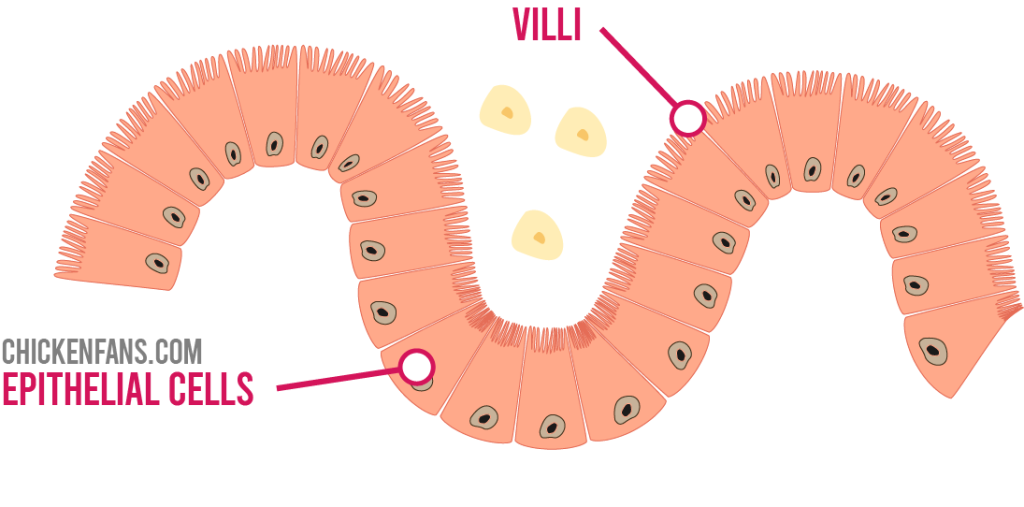

The inside wall of the bowels contains villi, which look like tiny fingers sticking out. They increase the surface and help in the absorption of nutrients. The inner linings of the intestines consist of columnar epithelium.

Large Intestine

Contrary to what the name suggests, the large intestine is only 4 inches long (~10cm). The large intestine is a continuation of the small intestine and ends up in the rectum and the cloaca.

There are much more bacteria in the large intestine due to the absence of bile. Bacteria in the gut microbiome play an essential role in digestion. They break down food, produce vitamins and nutrients, and profoundly affect the chicken’s health. The chicken’s diet heavily influences the microbiome composition. The bacteria involved are Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides.

The large intestine further reabsorbs most of the water in the bowels.

Ceca

Chickens have two ceca, blind pouches of about 7 inches (~17cm) that branch at the beginning of the large intestine. When food comes in via the small intestine, it’s first stored in the ceca to reabsorb water.

In the ceca, a fermentation process breaks down crude fibers. The bacteria in the ceca produce several B vitamins, like thiamine, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, and vitamin B12. However, since the large intestine is so short, it’s difficult for the chicken’s body to absorb all the produced nutrients.

When the water is absorbed, and most of the fibers are digested, the ceca empty the residual debris a couple of times a day in cecal droppings. These nasty-smelling, pasty droppings differ from normal droppings in color and consistency. Cecal poop sometimes worries chicken owners who think their chickens suffer from an illness. However, cecal droppings are perfectly normal.

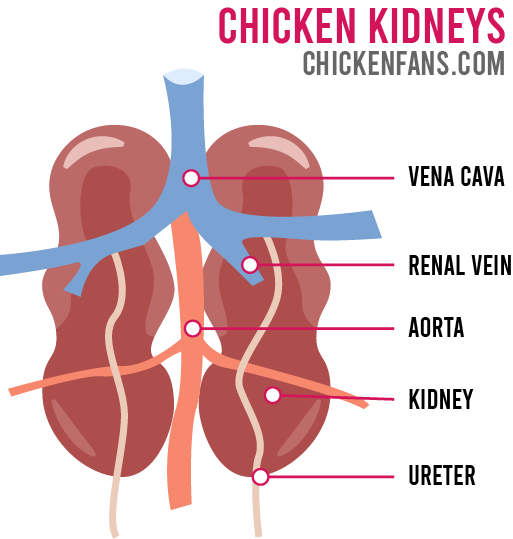

Kidneys

Chickens have two long kidneys, but they don’t pee and don’t have a bladder like us. The urates produced by the kidneys go directly to the cloaca via the ureter. In the cloaca, the urates mix with the droppings to form the moistened droppings as we know them.

The primary function of a chicken’s kidneys is to clean the blood.

The kidneys:

- remove waste and toxins from the blood

- regulate blood volume

- produce hormones that regulate blood pressure

- control production of red blood cells

When the kidneys are damaged, uric acid can build up in the blood and cause Gout. In the case of Gout, uric acid causes urate crystals on the joints, air sacs, and vital organs like the heart and liver. Gout can go unnoticed for a long time, resulting in almost sudden death.

Medication with diuretics is not as straightforward in poultry. Humans have evolved kidneys that reabsorb any nutrients like amino acids and glucose that would otherwise end up in the urine. This is accomplished via a complex chemical process that takes place in the Loop of Henle. Chickens, however, have very poorly developed loops of Henle and lose nutrients when treated with urate-increasing drugs.

Cloaca and Vent

The large intestine ends in the cloaca, together with the urinary and reproductive tract. The vent is the final opening of the cloaca to the outer world.

Egg laying

There is only one vent, so the eggs, droppings, and uric acid pass through the same opening. When a chicken lays an egg, the vagina folds inside out in the cloaca. This keeps the eggs separate from the droppings. In case of prolapse, the vagina fails to retract, a severe medical condition.

Droppings

If you inspect chicken droppings, you notice both white and dark parts. The darker material is the digested food, and the white parts are uric acid crystals, the chicken’s urine.

Bursa of Fabricius in Chickens

The Bursa of Fabricius in chickens is a lymphoid organ in the cloaca that produces B-cells from stem cells. It’s an essential part of the immune system of newly hatched chickens. Due to the involution of the bursa in chickens, the organ disappears after a year.

A viral infection of the bursa can cause Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) in young chicks. It’s a widespread contagious disease that suppresses the immune system and poses challenges for the poultry industry.

Pasty Butt

Pasty Butt or Pasty Vent is a condition where the chick’s vent is clogged up with dried droppings. It’s a life-threatening situation.

When chicks switch from yolk nutrients to normal feed, the digestive system is switched on. Chicks can dehydrate when the brooder is too hot, which indirectly causes the ceca to lose water. Because of the lack of water, the microbes in the ceca can’t properly digest the fibers in the food, and the cecal droppings become much more sticky.

Young chicks cannot push out the mix of the pasty cecal poop and the normal poop. The final result is Pasty Butt in chicks.

Chicken’s Digestive System vs. Human Digestive System

Although there are several similarities to our digestive system, there are also significant differences. The table below lists the most prominent differences between the chicken and human digestive systems.

| Chicken Digestive System | Human Digestive System | |

|---|---|---|

| mouth | beak, tongue, no teeth or cheeks, hard palate with choanal slit | teeth, cheeks, soft and hard palate |

| throat | crop to buffer food | no crop equivalent |

| stomach | proventriculus for chemical digestion and a muscular gizzard with grit | single stomach, we use teeth to break down food instead of stones in the stomach |

| liver | continuous bile secretion system that allows for constant digesting | uncomplicated bile secretion system to the intestines |

| ceca | two ceca to break down fibers and plant-based cellulose | a single cecum joined to the appendix at the beginning of the large intestine helps with the absorption of salts and electrolytes |

| kidneys | produces uric acid | produces urine, well-developed Loop of Henle |

| cloaca | single vent for eggs, urinary tract, and droppings | separate openings for the urinary tract, reproductive tract, and feces |

Growth of the Digestive System in a Chicken Embryo

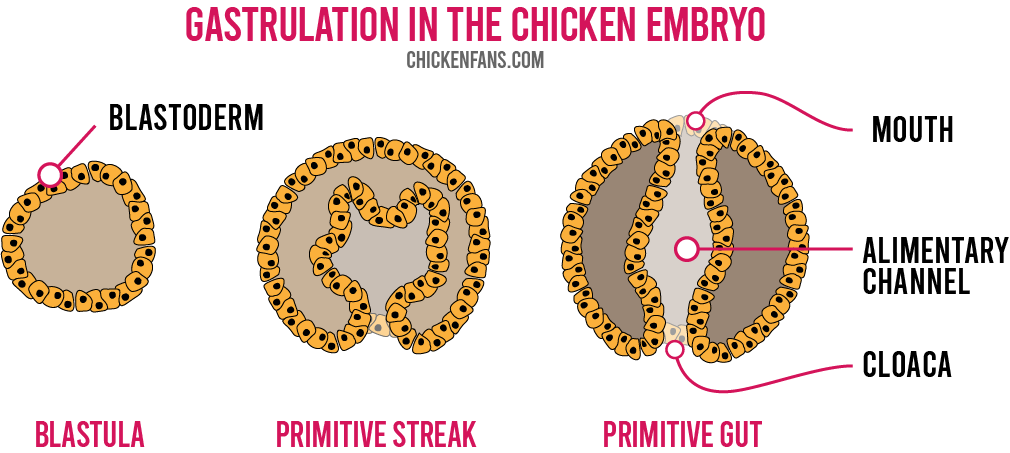

The alimentary canal is the muscular digestive tract that connects the mouth all the way through to the vent. This long canal is formed in the chicken egg’s early stages of embryonic development.

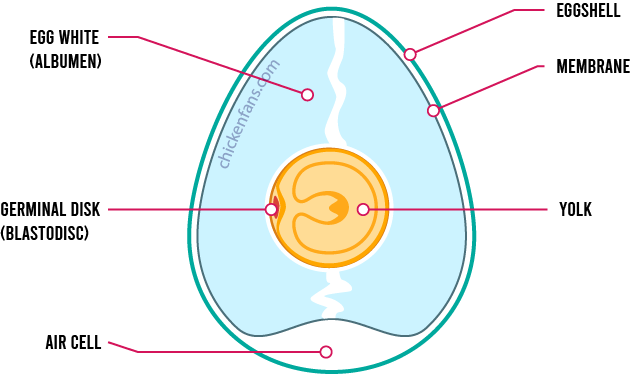

The early embryo develops in the germinal disk, a tiny spot in the yolk of a fertilized egg. The embryo starts as a couple of cells replicating and turning into a ball of cells, the blastula.

During the gastrulation phase, this ball of cells turns into a multi-layered organism. The cells of the ball turn inwards during a process called invagination. This dent forms the primitive streak. It’s the point of no return that many biologists see as the beginning of life. The primitive streak will later turn into the vent of the chick.

During gastrulation, the cells continue to bend inwards until a channel is created that passes entirely through the embryo. This small channel is the primitive gut, scientifically known as the archenteron. The first opening will become the cloaca of the chick, and the second opening becomes the mouth. Biologists call chickens deuterostome, which is ancient Greek for ‘having two mouths.’

All the digestive organs, like the intestines, stomach, liver, and pancreas, will grow from these inner linings of the alimentary canal.

Appetite Regulation in Chickens

Chickens seem to be eating all day long, giving the impression that they are always hungry. Meat chickens eat even more than free-ranging laying hens.

For most animals, satiety is entirely orchestrated in the brain. In chickens, the liver also plays an important role. It reacts to high blood glucose levels, decreasing feed intake. The satiety is mediated by the cholecystokinin hormone, released in the small intestine.

Chickens generally have high blood sugar levels to support their active lifestyle during the day. When the glucose levels become too low, the hypothalamus in the chicken brain will increase the appetite. When the pancreas becomes hyperactive, secretes too much insulin, and causes blood sugar levels to drop, there is an abnormally increased appetite for food.

Control of the Chicken’s Digestive System

The activation of the digestive tract in chickens is controlled by peripheral hormones and via the hypothalamus in the brain. The nervous system triggers the production of saliva when the chicken sees, smells, or tastes food.

Several hormones stimulate the production of enzymes:

- gastrin stimulates the secretion of gastric juice in the proventriculus of a chicken

- secretin stimulates the secretion of pancreatic juice for the small intestine

- cholecystokinin stimulates the release of bile from the gall bladder and regulates satiety in chickens

Body fat has become a problem in the poultry industry for broiler chickens. There is specific commercial interest in controlling satiety via peripheral appetite-reducing hormones.

Summary

The chicken’s digestive system is an ingenious system that processes food in multiple phases. The digestive tract has many similarities to ours, but significant differences exist.

Our birds don’t have teeth, and their gizzard stomach breaks down food with grit and stones. Chickens have a crop to buffer food and have two ceca to break down plant-based material. This results in cecal droppings that differ from normal droppings.

Chickens don’t have a bladder, and the urinary tract ends in the cloaca together with the reproductive tract. Although the eggs come through the same opening as the droppings, the eggs stay clean because the vagina folds inside out in the cloaca.

When a chicken eats, the food travels from its mouth through the entire alimentary canal to the cloaca. This alimentary canal is the first thing that develops in the chicken’s embryo. The early embryo consists of the mouth and vent openings connected via a channel. The complete digestive system grows from the inner linings of the early alimentary canal.

Although chickens always seem to be eating, their appetite and satiety are controlled by their brains and multiple hormones. These hormones stimulate the secretion of digestive juices containing enzymes that break down food in the stomach and intestines.