Marek’s Disease in Chickens (2024 Updates)

Marek’s disease is a common viral disease out in the wild that can wipe out 80% of an unvaccinated flock. The symptoms are horrendous as chickens become paralyzed, blind, and grow cancer tumors. It’s highly contagious, and there is no cure.

Worldwide vaccination has drastically lowered the incidence of Marek’s disease in chickens. But over the years, the virus became more virulent, and recently, some variants could break through the best vaccines on the market. Should we be worried?

Every chicken owner should know about Marek’s disease and how to deal with it.

- What is Marek’s disease?

- Symptoms

- Treatment

- Transmission

- Is Marek’s disease contagious to humans?

- Stages of infection

- Vaccination

- The problem with Marek’s Disease Vaccines

- Historical evolution of Marek’s Disease Virus

- Mechanisms of Marek’s disease virus

- Summary

What is Marek’s disease?

Marek’s disease is a common viral disease in chickens caused by the herpes virus.

The herpes virus manifests in awful ways:

- it attacks the nerves and paralyzes the legs, wings, and neck

- it grows tumors on the bird’s heart, ovary, muscle, lungs, and feather follicles

Chickens that are infected become infected for the rest of their life. That doesn’t always mean they get sick, just that they carry the virus and can spread it. Marek’s disease is so widespread that every flock in the world is presumed to carry the virus.

The virus is highly contagious and usually spreads through the dust in the air. Multiple virus variants exist, ranging from very mild to very virulent. There is no cure, but vaccines exist. Most vaccinated birds won’t get (too) sick.

The disease is named after József Marek, who described it first in 1907.

Symptoms of Marek’s disease

It’s not always easy to recognize the symptoms of Marek’s disease. There are several different symptoms and some birds even die without showing any clinical signs.

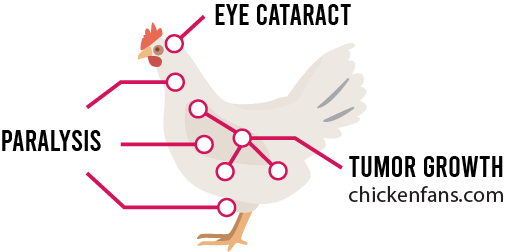

The virus manifests in two forms: the nervous form and the visceral form.

Nervous Form

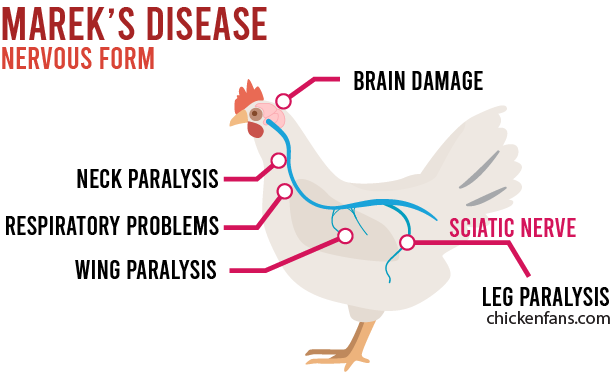

In this form, the virus attacks the nerves of the chicken. Depending on the specific nerves under attack, the symptoms can vary.

Due to nerve damage, the chicken becomes more and more paralyzed over time. This can go very fast.

It usually starts with the legs because the virus attacks the largest peripheral nerve in the chicken’s body: the sciatic nerve. This nerve runs from the chicken’s tail and thigh to its knees and operates the main leg muscle.

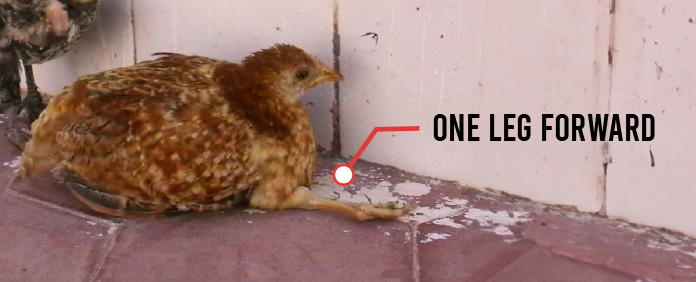

The paralysis often begins on one side, causing them to sit with their legs splayed. Typically, you’ll see chickens with one leg stretched out in front of them.

When the legs go limp, the chicken can’t stand anymore and waddles around uncoordinated, falling to the ground. They can’t reach their water and food and get weaker over time.

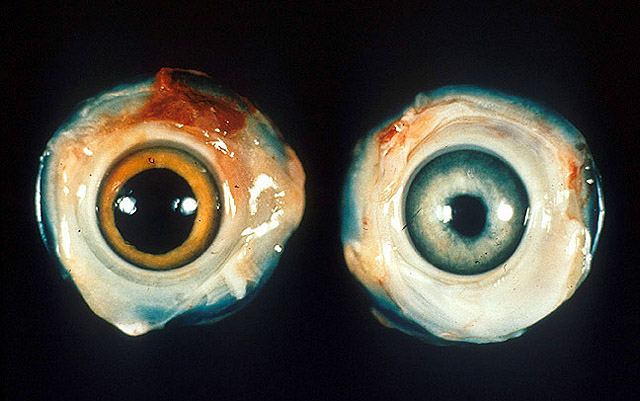

The paralysis can also progress via the nerves of the neck and wings, rendering the bird helpless. Sometimes, the eye nerves become infected, growing cataracts in the eye and turning the chicken blind. You can spot this when the iris turns grey and the pupil gets distorted.

In the last 20 years, more and more virus strains can also inflict brain edema. This can cause temporary paralysis of the neck and legs for up to two days.

Visceral Form

As if the nervous form is not enough, there is an even worse form. Marek’s is causing viral cancer in chickens and grows tumors on the internal organs. This affects multiple organs, including the chicken’s heart, ovaries, liver, spleen, and kidneys.

Unfortunately, this is very common, especially in unvaccinated birds. It can kill up to 80% of your flock.

In this case, the outer symptoms are less obvious, but you might notice:

- a pale comb indicating anemia

- a shrunken comb indicating dehydration

- (green) diarrhea

The symptoms vary depending on the virus strain and the organs affected. Since most manifestations occur inside the body, it’s not always easy to diagnose. It’s not that the external symptoms are less pronounced, but they also appear in several other situations.

For example, a pale comb is caused by anemia, a condition where the blood can’t carry enough oxygen. But a pale comb is also a symptom of many other diseases like coccidiosis. It can even result from something seemingly innocent, such as eating rhubarb leaves.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis using a feather is possible in the lab but can give false positives since most birds carry the herpes virus for life. A full autopsy to check for tumors is the most reliable way of diagnosis.

Treatment

Unfortunately, there is no effective cure for Marek’s disease in chickens at this point in time.

It will spread quickly when your flock is introduced to a new virulent strain they never encountered before. The disease shows up most frequently in unvaccinated chickens younger than 30 weeks. But older birds and vaccinated birds can get sick, too.

Treatment is focused on isolating the infected birds from the flock. You can medicate against suffering from symptoms, but in severe cases, the recommendation is usually to euthanize the chickens, as very few recover from malignant tumors.

When you diagnose an infected chicken, chances are high that other birds are also infected. So keep an eye on the rest of the flock. Always practice good biosecurity during treatment to prevent transmission as much as possible.

Transmission

The herpes virus is highly infectious and circulates rapidly in a flock. Spread is always fast, whether the chickens are vaccinated or not. The virus is released from the feather follicles and travels in dander and dust particles. Chickens become infected when they inhale the virus particles.

Spread

The dust naturally spreads in the wind and with birds scratching the soil. Virus particles easily attach to clothing and shoes. It’s common to bring new virus strains from other flocks, especially because it is so widespread.

The herpes virus can survive multiple months outside a chicken’s body. Sometimes, even years. An infected bird carries the virus for life and can always spread it. When a chicken is vaccinated, the dander will contain fewer virus particles, but they will still be contagious.

In fact, vaccinated birds are the most dangerous. They will suppress mild strains of the virus but spread the lethal strains rapidly. Unvaccinated chickens will quickly die from the most severe strains, which stops the virus.

| Mild virus strains | Severe virus strains | |

| Unvaccinated chickens | plenty of virus particles spreading | dead before spread |

| Vaccinated chickens | virus suppressed, no spread | plenty of virus particles spread |

Many birds carry the virus passively, similar to the herpes virus in humans. It is presumed that almost every flock has a bird that carries a virus strain.

Luckily, the virus can not be transmitted from a hen to her eggs. Furthermore, the antibodies of the mother hen protect the baby chick in the first days of its life, which gives the chicks some time to develop their immune system.

Transmission between chicken breeds and turkeys

The severity of the disease varies per breed. Light egg layers and silkies are more susceptible to the virus than their heavyweight counterparts.

The chicken herpes virus can spread to quails, and some newer severe strains can invade turkeys. The turkey herpes virus, on the other hand, can not spread to chickens and is commonly used as the base of vaccines for Marek’s disease.

Is Marek’s disease contagious to humans?

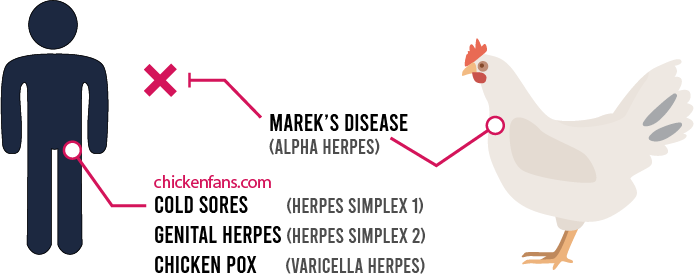

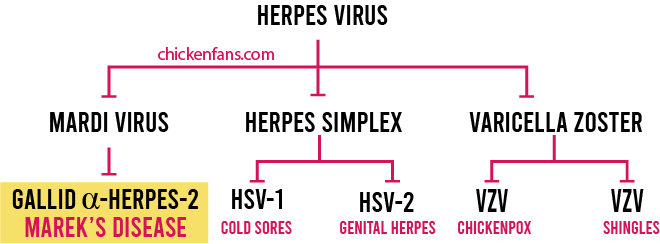

No, the herpes virus strains that cause Marek’s disease are not contagious to humans. These strains affect only chickens, turkeys, and quails. In a sense, we are lucky because Marek’s herpes virus is closely related to human variants.

It is in the same family as the human herpes variants. In humans, the most well-known herpes viruses are chickenpox (varicella-zoster), cold sores, and genital herpes (herpes simplex). All these viruses are genetically very closely related, especially in the unique regions of the DNA that characterize the herpes viruses. They have the same appearance if you look at them with a microscope.

A significant difference is that the human variants do not contain the genes that are needed to code proteins for tumor growth.

Stages of infection

The Marek’s disease virus is a complex herpes virus that goes through three stages of infection:

- initial infection: the chicken inhales the virus, and the virus starts the first round of replication to invade the immune system in the lymphoid organs

- dormant phase: the herpes virus silently settles itself inside the killer T cells of the chicken’s immune system. There are no real symptoms yet in this latent stage. The virus uses the T cells as a Trojan Horse to travel through the body. When the virus particles arrive at the feather follicles, they assemble and transform into contagious dander.

- active phase: the virus wakes up and activates. It starts growing tumors and affects multiple nerves in the chicken’s body, resulting in progressive paralysis.

These stages are similar to the phases of the human herpes virus.

Vaccination

It’s impossible to prevent infection with Marek’s disease; it’s too widespread. Virtually every chicken worldwide already faces the virus on its first day of life.

That’s why it’s essential to vaccinate chicks as early as possible. Preferably before they come in contact with the virus. Directly injecting the vaccine into the egg on the 18th day of incubation is the most effective. Vaccination can be combined with vaccination for other diseases and probiotics. Chicks that get probiotics during vaccination show a better immune response.

Hatcheries rely on automated vaccination technology to execute in ovo injections with surgical precision. If injecting the egg is not an option, vaccination on hatching day is an alternative. Keep the chicks isolated and apply proper biosecurity so they won’t come in contact with the virus before developing immunity.

Vaccine distribution targets big hatcheries. Not all areas have singular doses available for backyard chickens. If that’s the case for you, the best way to get vaccinated chickens is to buy them at a hatchery.

Vaccination will never prevent infections, but it will reduce the severity of the symptoms and significantly improve recovery.

Vaccine development

Since 1960, vaccines have been available based on the turkey herpes virus, which does not cause the disease in chickens. Later, other vaccines containing a weakened version of the herpes virus were developed. Some vaccines are genetically modified to combine vaccination for other poultry diseases like Newcastle disease, one of the top 5 causes of death in chickens worldwide.

Back in 1960, the vaccines reduced the incidence by 99%. It was a true landmark since it was the first vaccine that provided immunity against a cancer that routinely took out more than 90% of a flock. Unfortunately, the virus has evolved since then, and vaccines are not as effective as they used to be.

The problem with Marek’s Disease Vaccines

The herpes virus causing Marek’s disease continuously evolves and finds ways to overcome the existing vaccines. At the same time, the underlying principles of the immunization effect of vaccines are not yet completely understood. The vaccine boosts the immune system and prevents cancer outbreaks but can’t completely stop the disease. It stays dormant in the chicken’s body.

According to Andrew Read from Pennsylvania State University, vaccines are why the virus has become more aggressive over the years. The vaccine is leaky. A vaccinated chicken can still pass on the virus. And they pass on the most virulent strains.

Vaccinated chickens suppress mild viruses superbly. But the birds will happily carry around the severe varieties, whereas the unvaccinated chickens would have died. This buys the lethal strains some extra time to spread in the dust. The result is a virus that becomes progressively worse.

Vaccines have been based on combinations of the turkey herpesvirus and CVI988-Rispens strains for years. But since 2020, some herpes superstrains have been circulating that can break the vaccine protection in chickens. Even with the most effective vaccine combinations in use. Richard Witter, one of the founding fathers of Marek’s disease vaccines, already warned us of this scenario in 2004.

Modern vaccine development might shed some light on the end of the tunnel. Recent advances in genetic virology and complete DNA sequencing of the chicken’s genome are opening new pathways for vaccine development. Due to obvious commercial interest, much research is currently being funded. For example, researchers are applying CRISPR/Cas9 to create new avian herpes virus recombinant vectorized vaccines.

But as long as no alternative is found, the clock is ticking.

Update on Marek’s Vaccines Effectivity on 25 June 2023

Recently, MD outbreaks have been frequent in vaccinated chicken flocks, but the key factors and determinants behind this remain unclear.

A study in China analyzed the pathogenicity of seven newly isolated MDV strains from chickens with tumors and found that all were pathogenic. Four of these strains were considered hypervirulent MDV strains. In an experimental infection, these HV-MDV strains resulted in high cumulative incidences and mortalities of MD, as well as tumor occurrences and damage to immune organs.

The study also examined the effectiveness of four commercial MD vaccines (SDCW01, CVI988, HVT, CVI988+HVT, and 814) against these HV-MDV strains. Surprisingly, the vaccines showed low protection indices, and even the monovalent CVI988 or HVT vaccines still led to tumor development in a small percentage of birds.

This study highlights the challenges posed by HV-MDV strains and the need to develop more effective vaccines to control MD in the future.

Vaccination and Backyard Chickens

Backyard chicken farming is becoming increasingly popular across both rural and urban areas in the United States. Many backyard chickens are heritage breeds or modern hatchery mixes. These backyard chickens also contribute to the spread and persistence of various infectious diseases such as Marek’s.

Unlike chickens bred for commercial purposes, there has been less extensive research into the immune system and disease resistance against Marek’s Disease.

A study published in Poultry Science in 2024 investigated how different breeds of chickens respond to viral infections. They used synthetic double-stranded RNA to stimulate the immune system through the MDA5 pathway, which is important in the body’s defense against viral infections like Marek’s Disease Virus.

Interestingly, there were significant differences in the immune response among different breeds. Breeds like the Barred Plymouth Rock, Rhode Island Red, White Leghorn, and Red Ranger Broiler generally show a better immune system response. It seems that those breeds have a better innate response to viral infections such as Marek’s Disease.

Historical Evolution of Marek’s Disease

Since its initial recognition, the virus has evolved dramatically, with more terrific symptoms showing up over the years. At this time, a full range of virus strains will affect the chicken in different ways. The classification goes from mild (m) to virulent (v), very virulent (vv), and very virulent plus (vv+).

Some vv+ strains, like the GX18NNM4 strain, are able to break through the best vaccines on the market.

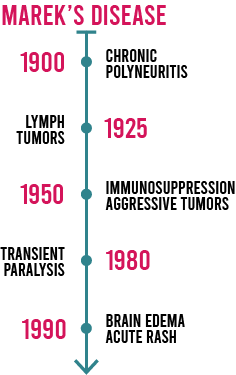

A quick glance at the evolution chart tells us that the virus is not planning to stop evolving.

- in 1900 the disease started as a chronic disease that only affected the peripheral nerves of the chicken’s body

- from 1925 the disease evolved and started to grow visceral lymph tumors

- around 1950 the virus created more aggressive tumors that could suppress the immune system

- in the eighties, the virus started to affect more and more nerves, ultimately leading to the associated paralysis and death

- in the nineties, some virus strains started causing brain edema (fluid in the brain), widespread damage to the brain and central nervous system, and acute rashes

The clinical picture of the disease is continuously evolving beyond paralysis and cancer tumors. We are now at a saddening point where people report acute deaths, even in fully vaccinated chickens.

Marek’s disease threatens chicken flocks worldwide, and this sword of Damocles may descend at any moment.

Mechanisms of Marek’s Disease Virus

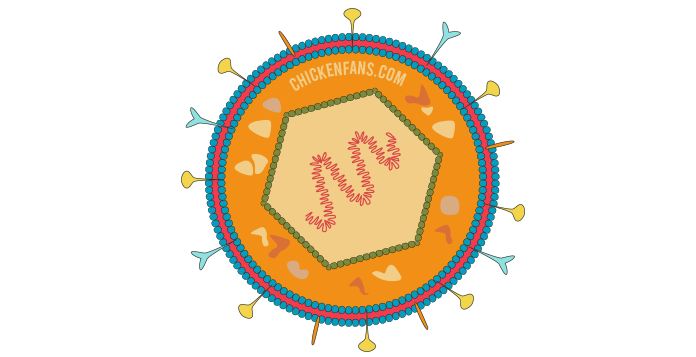

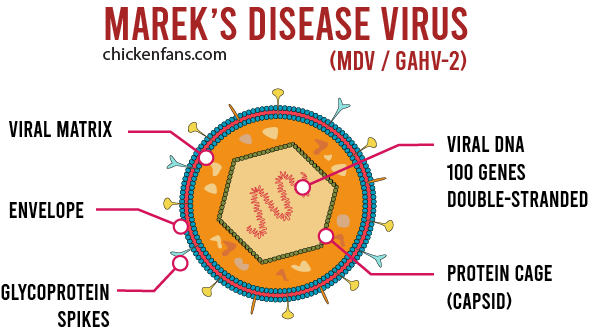

Marek’s disease virus (aka MDV) is a herpes virus and certainly not your typical next-door neighbor virus.

From the outside, virus particles look spherical, with spikes, similar to the COVID-19 virus. The viral load is stored in about 100 genes of DNA, stored centrally in an icosahedral protein cage.

The surface is loaded with glycoprotein spikes, which help the virus attach to the chicken’s cells.

Replication Stages

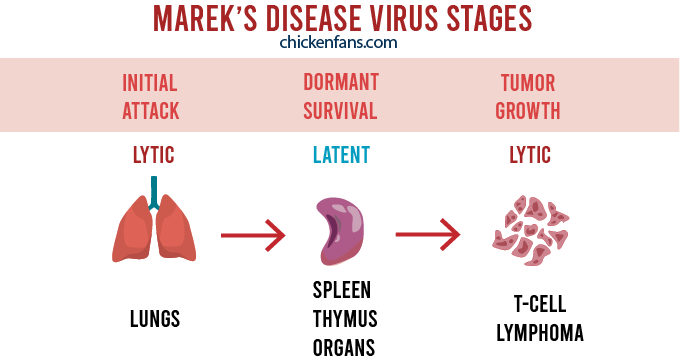

Marek’s disease virus has the remarkable ability to stay silent in the chicken’s body. This stage is called the latent stage of the virus.

The virus also has an active stage, producing thousands of new virus particles. An active virus attacks the chicken’s nerves and organs. This is called the lytic stage.

When a chicken inhales the virus, it will tactically apply both stages during the invasion.

- Directly after inhalation, the virus replicates and attacks the lungs to establish ground. This process is lytic.

- Then, the virus hijacks white blood cells and travels to the spleen, thymus, and the bursa of Fabricius. The bursa is an organ in the immune system that only exists in birds. There, it stays latent to survive and infect more organs. This is a latent stage.

- At the same time, the virus also travels to the feather follicles to infect the skin. This process uses both latently and lytically infected cells.

- When the virus has enough presence in the body, some infected killer T-cells of the immune system will grow tumors.

When a chicken recovers from Marek’s disease, the viral DNA stays dormant in the chicken’s body.

The ability to move back and forth between latent and active phases is what makes the virus difficult to tame.

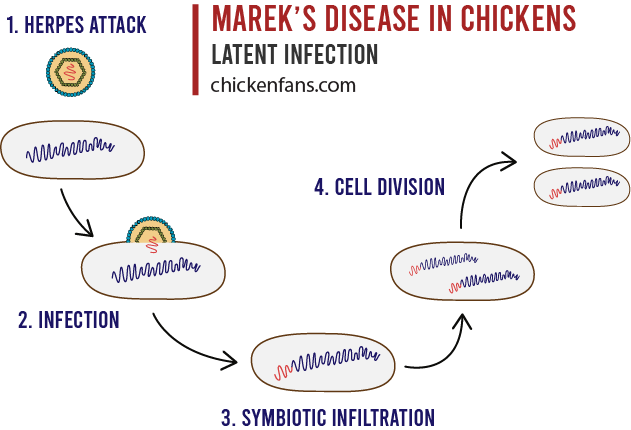

Latent Infection

When the herpes virus attacks, it attaches itself to the cell wand of the chicken’s lung cells. The virus opens a funnel to inject the viral DNA into the host cell. This viral DNA contains the unique receipt to create more Marek’s disease virus particles later on.

The DNA is similar to that of human herpesviruses like Varicella, the virus causing chickenpox. But Marek’s disease virus contains some extra genes. For example, those that describe how to encode proteins for cancerous tumor growth. Depending on the strain of the virus, these genes will provoke mild or severe symptoms.

In the 100 years of co-evolution with our chickens, the disease has found new and creative ways to infect target cells. Some of its tactics are based on genes that were pirated from the chicken’s DNA and tweaked for infection. These days, it can generate biochemicals like viral interleukin-8 (vIL-8) that are very peculiar to a chicken’s biochemistry.

The latent phase of Marek’s disease begins about seven days after the initial infection of the chicken. The DNA strains reside in the chicken’s cell without destroying it or provoking excessive damage. By staying silent, the chicken can survive and keep the virus alive. Cell division in the chicken’s body is unchanged and can go on as usual.

The Invisible Virus

One of the extraordinary capabilities of Marek’s disease virus is that it can downregulate the major histocompatibility complex of a chicken. Normally, when a body cell is infected, the cell will collect all the glycoprotein spikes of the virus and present it on a tray to the killer T-cells of the immune system for inspection. When the immune system notices foreign proteins, the cell is killed. But the smart Marek’s virus contains genes that can bypass this mechanism.

As a result, the virus-infected cells are invisible to the chicken’s immune system and the killer T-cells. To make matters worse, in the latent phase, the virus mainly resides inside the immune system T helper cells (CD4+ cells). This makes it virtually impossible for scientists to know how many cells in the chicken’s body are infected with the virus.

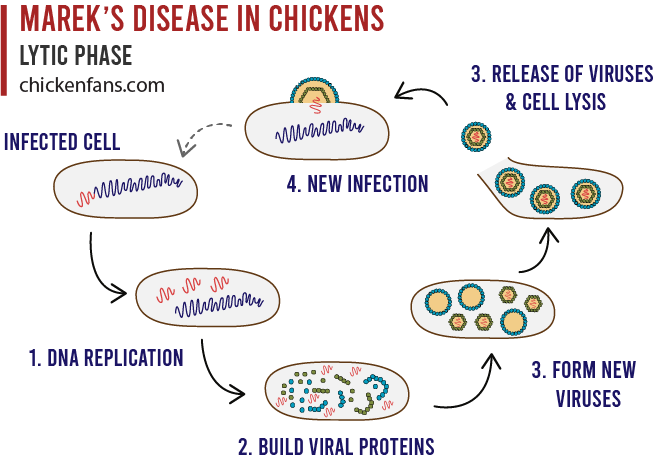

Lytic Phase

When a chicken becomes infected with Marek’s disease virus, it spreads through the body. Every time the virus infects a cell, it injects its viral DNA into the chromosomes of the cell. The virus replication peaks somewhere between the third and seventh days after the infection.

In the lytic phase, this DNA is replicated and used as a prescription to build new viral proteins. Since the virus is smart enough to suppress the immune system, this build-up of proteins goes undetected.

The virus hijacks the cell’s mechanisms to generate as many viral proteins as possible. These proteins are the building blocks to fastly create new copies of the virus. At a certain point, there are so many copies that the cell bursts, and the viruses are released into the chicken’s body. A key difference with the latent phase is that the cell wand is ruptured, and the cell is destroyed (lysis).

The virus reaches the skin of the chicken after five days. However, the development of rashes follows much later. The virus is believed to spread to the skin and organs using both lytic and latent replication mechanisms.

Tumor Growth

Tumors start to grow in the chicken within three weeks after infection. Cancer development in the T cells of the immune system is a very complex process. Only a small subset of the infected cells will start to grow tumors. Some tumors might even originate from a single cell. Since so few cells grow tumors, the virus must infect a substantial amount of cells for the chicken to risk cancer development.

The transformation of the cells into malignancies is still being heavily researched. One of the key biochemicals in the process has the codename Meq, and was only discovered by researchers in 1992. It’s a basic leucine zipper that transcodes DNA to build cancer proteins. This basically means it’s taking different parts of DNA strings and tying them together to build cancer as if they were the laces of a shoe.

Summary

Marek’s disease is a terrible disease in chickens caused by the herpes virus. It causes paralysis, tumor growth, and, ultimately, death.

Vaccination has proven effective, but some virus strains recently evolved to overcome the best vaccines. The only way to prevent the disease is to vaccinate chicks early.

However, vaccination will not prevent a viral infection, and it is so widespread that it’s assumed that every chicken worldwide will somehow face it during its lifetime. Once a chicken is infected, it stays infected for life since the virus can remain dormant in the chicken’s body.

Dr. M. Tanveer is a licensed veterinarian with several years of experience with chickens. He got his degree from the Faculty of Veterinary and Animal Sciences of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur and has firsthand experience as a veterinarian on broiler breeder farms.